Women bear the brunt of the costs, both financial and emotional, when their loved ones are incarcerated. According to a recent study by the Ella Baker Foundation for Human Rights, in 63% of cases, family members on the outside are primarily responsible for court-related costs associated with conviction, and of the family members primarily responsible for these costs, 83% are women. This is especially problematic for black women, since their family members are five times more likely to be incarcerated than their white counterparts.

This impacts black women and their families more significantly than others, deepening inequities and societal divides that have pushed many into the criminal justice system in the first place, since two out of every five Black women are related to someone who is incarcerated. This can further jeopardize their own stability, since the family’s financial burdens disproportionately fall upon women in the family who may also have children living at home. For example, almost half of family members primarily responsible for paying court-related costs are mothers, and one in ten are grandmothers.

Specifically, the costs associated with incarceration include phone calls, visitation, commissary, and health care, which often result in severe financial consequences for families on the outside. One in three families (34%) reported going into debt to pay for phone calls or visitation. Often, families are forced to choose between supporting incarcerated loved ones and meeting the basic needs of family members who are outside. Research conducted with visitors at San Quentin State Prison in California showed similar results. The majority of women in that study reported spending as much as one-third of their annual income to maintain contact, and for a number of these women, including many who are mothers, these costs often put them into debt.

Further barriers exist based on race and ethnicity, including fewer jobs for black people previously incarcerated, as well as restrictions on travel. For Latinos, documentation status is a more likely barrier to finding work. These challenges only serve to prolong the financial burden placed on women and these families.

For women of color, the financial load that comes with supporting a loved one in prison is often amplified by the reality that there is no Equal Rights Amendment in the US Constitution. The ERA would help ensure that women, of all races, would have the right to employment earnings equal to white, non-Hispanic men (the highest income earners in the US). According to the 2017 census, black women were paid only 63 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men. And even in states with large populations of Black women in the workforce, rampant wage disparities persist, with potentially devastating consequences for Black women and families.

Black women in the District of Columbia, for example, are paid only 52 cents, in Maryland only 69 cents, in Pennsylvania just 68 cents, and in Mississippi only 56 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men. Further, Black women in Louisiana are paid just 47 cents, in Texas only 58 cents, and in Utah,just 52 cents for every dollar paid to a white, non-Hispanic man. One could only imagine how much easier it would be for Black women to support themselves and their families while a family member is incarcerated if the ERA were included in the Constitution.

What would it take to ratify the ERA? There are two options, really:

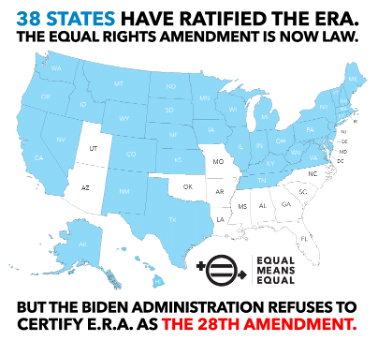

The traditional constitutional amendment process is described in Article V of the Constitution, where Congress must pass a proposed amendment by a two-thirds majority vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives and send it to the states for ratification by a vote of the state legislatures. The amendment becomes part of the Constitution when it has been ratified by three-fourths (currently 38) of the states. This process has been used for ratification of every amendment to the Constitution thus far. Article V makes no mention of a time limit for the ratification of a constitutional amendment, and no amendment before the 20th century had a time limit attached to it.

The second option is the three-state strategy for ERA ratification, which was developed following the 1992 ratification of the “Madison Amendment” as the 27th Amendment to the Constitution after a ratification period of 203 years. Given that acceptance, some ERA advocates contended that the ERA's ratification period of just over two decades would surely meet the “reasonable” and “sufficiently contemporaneous” standards required by Supreme Court decisions in 1921 and 1939. Time limits were not attached to proposed amendments until 1917, and Congress demonstrated its belief that it may alter a time limit in a proposing clause by extending the original ERA deadline. Precedent regarding a state’s ability to withdraw its ratification by a rescission vote shows that such actions have not been accepted as valid. Thus, supporters argued, the 35 existing ratifications should still be legally viable, and Congress likely has the power to adjust or repeal the previous time limit on the ERA, determine whether state ratifications subsequent to 1982 are valid, and recognize the ERA as part of the Constitution after three more states ratify.

This mode of ratification is getting closer to potential realization. With the ratification of the ERA by the state of Nevada in 2017 and by the state of Illinois in 2018, one more state is needed to ratify the ERA to achieve the initial 38 states for federal ratification as determined in 1982. If one more state ratifies the ERA, the ratification process will move into the courts for determination regarding the constitutionality of the original deadline that was originally applied

The states that have not ratified the ERA yet include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah and Virginia, Currently, bets are on Virginia to become the 38th state, which could be done as early as its next legislative session, starting in Richmond on January 9th, 2019

A recent graduate of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Sage Howard is a 2018 fellow in the Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program, funded by the Sy Syms Foundation. The Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program at Women’s eNews fellowship supports editorial and development opportunities for editorial interns in the pursuit of journalistic excellence.

A recent graduate of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Sage Howard is a 2018 fellow in the Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program, funded by the Sy Syms Foundation. The Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program at Women’s eNews fellowship supports editorial and development opportunities for editorial interns in the pursuit of journalistic excellence.