In the United States, 75 percent of incarcerated women are also their children's primary caregivers. And while these women are spending time in prison, their children are often spending time in some form of foster care.

For women of color, these numbers are even more staggering, The Pew Charitable Trusts found that one in nine black children have a parent incarcerated, compared to only one in 57 white children. These numbers are directly linked to statistics showing that of the 219,000 incarcerated women in the United States, two-thirds of them are women of color. Further, a significant number of women who are incarcerated are not even convicted, and more than a quarter of women who are behind bars have not yet had a trial.

This data is particularly problematic for women of color: Black women are going to jail at higher rates than their white female counterparts, a significant number of these women have been convicted of only minor offenses, and a large percentage of these women are losing care of their children until their release. Clearly, the effects of mass incarceration extend beyond the individual cells that hold black women back by disrupting the lives of the people who need them most.

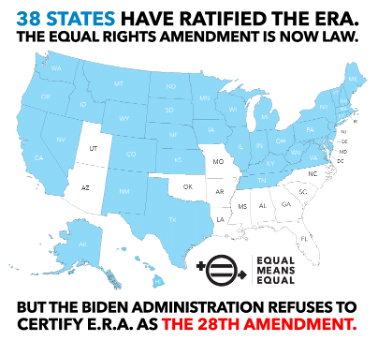

Since the US Constitution still does not include an Equal Rights Amendment, black women have even less protection under the law. They are less able to afford bail, since they are paid just 61 percent of what non-Hispanic white men are currently paid. This causes more black women to remain in jail while awaiting trial, causing their children to become hidden victims.

Currently, there are 2.4 million hidden victims living in the shadow of their parents’ incarceration. When a court therefore determines the fate of a primary caregiver, it is also determining the fate of the child she is caring for. While a mother serves time, her child may only be allowed limited visits, or in some cases, no visits at all. This lack of support can have harsh effects on children's overall wellbeing, both from a financial and mental health standpoint.

To try to keep their children with family members, 45 percent of incarcerated mothers rely on their children's grandparents to raise their children. But, according to the Prison Fellowship, as much as 80 percent of these children end up in households where there is extreme financial strain. The Urban Institute Justice Policy Center found that for children who live with their grandmothers, one in four of these children lives in poverty. Further, 66 percent of their grandparents are not provided with any financial support to raise the child.

Children may also experience emotional side effects from having their mothers incarcerated for any period of time. Children between the ages of 2-6, for example, often suffer from separation anxiety, traumatic stress and survivor’s guilt. Children between the ages of 7-10 may develop poor self-esteem, an inability to deal with future traumatic stress, and even regressive behavior; and children between the ages of 11-14 may begin to reject limits to their trauma-reactive behavior. For children age 15-18, experiencing their own parent(s) in prison can lead to criminal behavior that may result in their own incarceration as well.

Of further concern to incarcerated mothers is the federal law, the Adoption and Safe Families Act, passed in 1997 by former President Clinton, which gives states the right to terminate parental rights for children who have been in foster care for 15 out of the last 22 months. While the purpose of the act is to prevent children from spending long periods of time in foster care, thousands of mothers have lost their parental rights to their children since the average sentencing time for a mother is 36 months. Leading to permanent separation from their families, these children are often placed in homes with strangers who are paid to care for them, or in state agencies where they run the risk of never being adopted.

Clearly, this vicious cycle, which begins with unfair and unequal wages particularly affecting women of color, further impacts the innocent lives of their children when their mothers are incarcerated. Adding the ERA to the US Constitution would help ensure that women are paid equally, thereby providing greater financial resources for women most affected by mass incarceration. And this, most importantly, will help keep mothers in the lives of their children.

A recent graduate of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Sage Howard is a 2018 fellow in the Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program, funded by the Sy Syms Foundation. The Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program at Women’s eNews fellowship supports editorial and development opportunities for editorial interns in the pursuit of journalistic excellence.

A recent graduate of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Sage Howard is a 2018 fellow in the Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program, funded by the Sy Syms Foundation. The Sy Syms Journalistic Excellence Program at Women’s eNews fellowship supports editorial and development opportunities for editorial interns in the pursuit of journalistic excellence.