(WOMENSENEWS)—As I scanned a fiction aisle at Barnes and Noble recently, I noticed an older man with a frighteningly sunny grin on his face making a beeline towards me. “Uh oh,” I thought. Here it comes.

His smile got wider. “Hello, honey!” he addressed me condescendingly, in that sickeningly sweet tone that adults reserve for drooling 3-year-olds and, apparently, me. “It just makes my day to see people like you out in the world, being so brave!”

People like me.

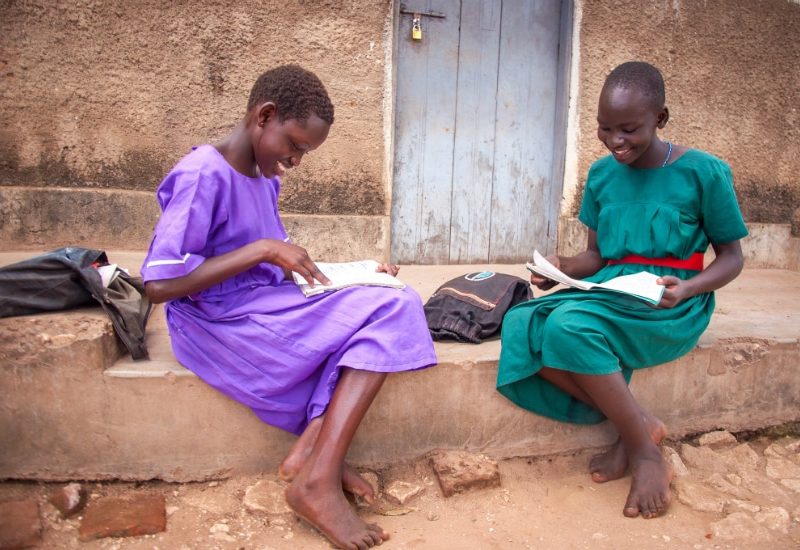

What our friendly grandpa was referring to, of course, was my wheelchair. I know, because this was not a unique occurrence. In bookstores, grocery stores, at the mall - basically any public place - people with disabilities around the world face uncomfortable encounters such as this one. Even putting aside this man’s condescending tone, his use of the phrase “people like you” furthers the all-too-common practice of separating people with disabilities from so-called “normal society.” My wheelchair made me a novelty to him, rather than a person, and a trip to the bookstore became a brave venture into a world that, in his eyes, did not belong to me.

This, my dear readers, is ableism. “Discrimination in favor of able-bodied people,” according to the Oxford English dictionary. But even this is an oversimplification. Ableism does not just mean choosing to build an entrance of stairs instead of a ramp, although this would certainly constitute favoring those who can walk over those who can’t. Rather, ableism is the misguided societal perception of those with disabilities as less capable, more pitiful and inherently different from able-bodied people.

It’s important to note that ableism is, in most cases, not purposeful. While racist or sexist comments are often intentionally discriminatory, ableism is so ingrained in our culture that people scarcely realize they’re propagating it at all. It’s not driven by hatred or hostility, like discrimination towards a different race or gender, but originates in misguided compassion and ignorant pity.

Just as Harmful

Yet, make no mistake, ableism is just as harmful and inexcusable as any other “-ism.” It portrays people with disabilities as a victim of their circumstances, negating paths towards personal empowerment or progress that are readily available to others. Ableism often becomes internalized in people with disabilities themselves, causing them to try and hide or minimize their disability because of shame or fear of ostracization. For most of my childhood, I’d shy away from any mention of my wheelchair or the things I couldn’t do. The very acknowledgement of my “difference” from another person could put me in tears and ruin my day, because I felt that anything deviating from being “normal” was problematic. Only as I’ve been in high school and have become more confident in my personal identity has this begun to change — but for everyone who has a disability, it’s an ongoing internal struggle.

This internalization of ableism is caused directly by the way people with disabilities are perceived in everyday life. Disabled women, in particular, face stereotypes of being unattractive, undesirable and passive. We are ceaselessly infantilized, called “sweetie,” “honey,” “cutie” and other names that imply we’re innocent, childlike and not to be taken seriously or respected as a mature person. No matter the age of a disabled woman, able-bodied people, and especially men, commonly refer to her as if she’s a young girl. This is a type of disrespect that able-bodied women often face in everyday life, too; but for women with disabilities, it’s even more common — just look at the man who addressed me as “honey” in the bookstore.

Another stereotype of disabled women is that we’re confined by our disability to being passive and unattractive. This was underscored only a few months ago when model Kylie Jenner posed for an Interview magazine photo shoot in a wheelchair, using it as a prop for her costume. Jenner explained the decision as a symbolic means of showcasing her apparent “limits” as a pop culture star — a complete misunderstanding of a piece of medical equipment that fosters freedom of mobility for those who need it.

Jenner isn’t the only one who misunderstands the meaning behind a mobility aid like a wheelchair, cane or walker. A constant theme as I’ve grown up has been both peers and adults treating my chair as a circus trick for their entertainment. No, it’s not funny when you make beeping noises as I back up; do people make a joke out of you as you take a step backward? Sorry, the buttons on my chair may make sounds, but that doesn’t make you entitled to enter my personal space and press them. How would you like it if I started getting up-close and personal with your legs? Right. And trust me, I don’t want to spend time answering the ceaseless “What does this button do?” because you think asking questions about the piece of machinery I sit in is equivalent to asking about me.

Threats to Physical Well-Being

But the implications of ableism span far beyond being simply degrading and offensive; women with disabilities even face threats to their physical well-being. A study from the School of Public Health at the University of Toronto found significant barriers to accessing reproductive health care for women with disabilities. Things like inaccessible equipment led women to avoid regular doctor’s visits, and insensitive health care providers expressed surprise that the study’s participants were even in need of reproductive care. This kind of discrimination is reprehensible; it assumes that these women are somehow less human because of their disabilities. Here, the stereotypes perpetuated by ableism created medical and attitudinal barriers that put them at risk.

Although Jenner may be looking for the public to pity her “limits” as a public figure, I promise you that people with disabilities have no need for anyone’s pity. Despite being physically different from an able-bodied person, people who have a disability can live a life that’s fulfilling and enjoyable. Contrary to the sentiments portrayed in the movie “Me Before You,” having a disability doesn’t immediately lead to a chronic desire to kill yourself. Although society has a penchant for driving the stereotype that people with disabilities live tough, miserable lives that no one could possibly bear, this sentiment is completely untrue. A 2012 study in the journal of Disability and Rehabilitation found that people with spinal cord injuries measured high in life satisfaction.

If getting up in the morning and going to the bookstore makes me your inspiration simply because I arrive on wheels rather than on feet, then, well, you might need to reevaluate your priorities.